Echoes of Exploitation

A Struggle for Survival: Samita's Story

“I want to quit my job because some colleagues try to lure me into do the wrong thing. They try and force me to do unethical things”

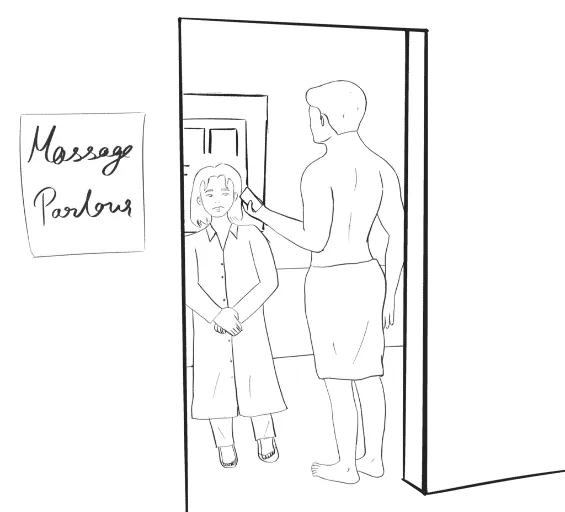

At just 14 years old, Samita works tirelessly for 12 hours a day at a massage and spa venue in Kathmandu, Nepal. After her family’s home was devastated by the 2015 earthquake, they moved to the city in search of a better life. However, the reality is far from ideal. Living with her ailing mother and younger sister, Samita feels immense pressure to provide for her family, often sacrificing her own well-being.

In her workplace, Samita earns a commission based on the number of customers she massages. Although she is paid NPR 500 (about $3.70) for each service, she also relies on tips, which range from NPR 100 to NPR 1,000 ($0.75 to $7.50). Despite her hard work, Samita often finds herself hungry, as she eats little at home and only snacks during her shifts. This hunger is compounded by her stressful environment, where she faces harassment from customers and pressure from older colleagues to engage in “unethical tasks.”

Samita’s struggle is further complicated by her tumultuous family life; her parents have been living separately for seven years, leaving her with little emotional support. Despite the difficult circumstances, she manages to find joy in dance classes and occasionally shoots music videos to earn extra money. However, the constant threat of harassment at work and the emotional toll of her home life leave her feeling trapped and alone.

In her own words, Samita expresses a desire to quit her job due to the pressure from her colleagues and the uncomfortable advances from customers. Yet, she

also acknowledges the stark reality of her situation: “I need to earn money for my family.” Samita’s story illustrates the heartbreaking reality faced by many children in similar situations, where the pursuit of survival comes at the cost of their childhood innocence.

Kakoli’s Silent Struggle: A Life Bound by Leather

“I only perform one task each day, it consumes my entire focus. I persevere without stopping. From 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., I dedicate myself entirely to this task.”

Kakoli, a 13-year-old girl living in Gojomhol, Dhaka, is one of many children forced into the harsh reality of child labor. She works in a leather goods factory, where her daily life is marked by long hours and monotonous tasks. To secure her job, Kakoli, like many of her peers, falsified her birth certificate, claiming to be 18. This deceit reflects the desperate measures children take to contribute to their families, as Kakoli’s mother, a factory worker herself, struggles to provide for her family.

Kakoli’s day begins early and stretches from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., during which she is wholly focused on weaving bags. Despite her commitment to her work, her life outside the factory is bleak. She rarely engages in recreational activities, with lunch breaks being her only moments of social interaction. While participating in CLARISSA research has brought her some joy by allowing friends to visit her home, Kakoli predominantly leads a life devoid of childhood experiences.

Her route to work is fraught with danger; Kakoli often encounters harassment from boys attempting to snatch her veil, leaving her feeling unsafe. The road is notorious for

rumors of drug use and violence, contributing to her anxiety about walking home alone. Kakoli describes her world as limited to her home and the factory, illustrating the grim reality for many children like her who are trapped in cycles of poverty and exploitation.

Kakoli’s story sheds light on the pervasive issue of child labor in Bangladesh, where children often sacrifice their education and childhood for survival. Her experience is a sobering reminder of the vulnerability of child laborers and the sacrifices they make to support their families.

Under the Scorching Sun: The Struggles of Sagir

“It is so hot that even the dogs jump in the river to cool off while I work.”

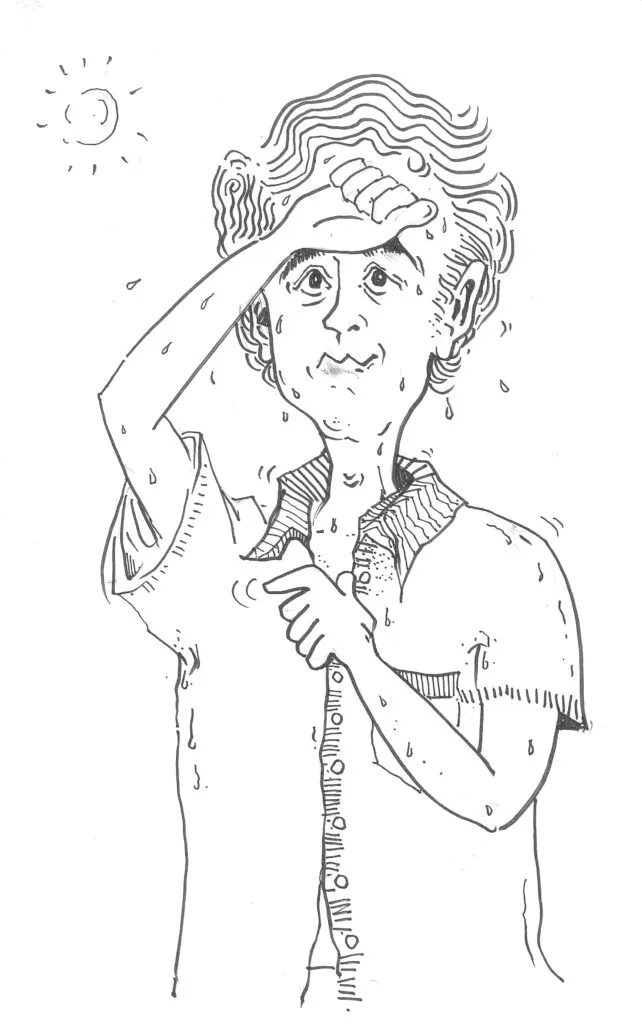

Sagir is a 14-year-old boy laboring tirelessly under the unforgiving sun in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Working 11 hours a day, he carries heavy leather hides and pins leather sheets to the ground to dry. The intense heat exposes him to considerable physical stress, and his small frame bends under the heavy loads. Motivated by the need to provide for his family, Sagir has sacrificed friendships and leisure time, fearing that socializing might lead him astray.

After relocating to Dhaka during the COVID-19 pandemic, Sagir’s life changed dramatically. He left behind his education when schools closed, and now he feels a deep disconnection from learning. He works on the banks of a river where he witnesses the extreme temperatures affecting not only himself but also the environment around him. “The sun is beyond human endurance,” he says, expressing the harsh reality of his daily struggle.

Sagir lives with his parents and younger brother, who is only six and not yet working. Both of his parents are also employed in the leather industry, which has become their family’s only means of survival since moving to the city. Sagir’s life exemplifies the tragic circumstances faced by many children forced into labor, highlighting the urgent need for advocacy and intervention to combat child labor in hazardous conditions

Hamisi: The Dark Depths of Desperation

“I nearly suffocated inside the pits due to an inadequate supply of oxygen.”

At just 11 years old, Hamisi has found himself trapped in the harsh world of mining after dropping out of school due to financial struggles. His family, who owned a small coffee farm in Tanzania, faced economic hardship as global coffee prices plummeted. With his father unable to afford school fees or uniforms, Hamisi decided to seek fortune in mining, lured by tales of wealth.

Using bus fare intended for necessities, Hamisi journeyed to Mererani, a mining town 70 kilometers from his home. Once there, he struggled to find work due to being a newcomer but eventually made connections with local children. He secured a position as a “service boy,” where his responsibilities included crawling down into dark, treacherous pits to deliver tools and bring water for the miners. The mining pits can reach depths of up to 300 meters and are notoriously hot and humid.

Hamisi describes the conditions: “The inside of the mining pit is totally dark… Our skin turns black because of the humidity and heat.” He often worked up to 18 hours a day, subsisting on just one meal of buns and boiled cassava, while struggling to breathe in the toxic dust surrounding him. The children working in these mines are colloquially known as “nyokas,” or “snake boys,” because of the way they navigate through narrow tunnels.

Although Hamisi and his peers are drawn to the mining sites by the possibility of discovering valuable gemstones, the reality is far from glamorous. Many only earn between 60 cents and $1.20 a day, and the chance of finding a gemstone is extremely rare. Despite his hopes of striking it rich, Hamisi’s experiences reveal the grim truth of child labor in the mining industry—a cycle of exploitation and disappointment that keeps children like him trapped in poverty